https://treskia.wordpress.com/

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/

http://m.facebook.com/treskia.org/

Seljuk Empire

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Seljuq_Empire

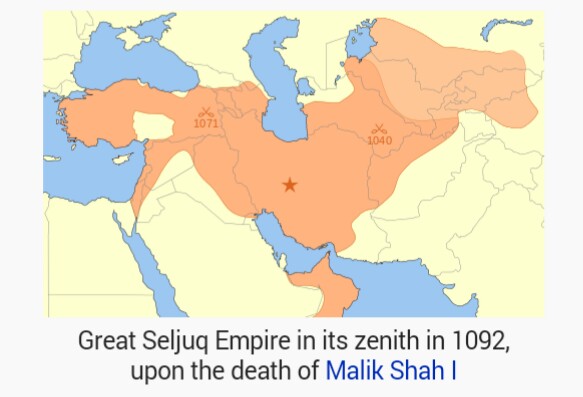

The Seljuk Empire was a medieval Turko-Persian empire, originating from the Qynyq branch of Oghuz Turks. The Seljuq Empire controlled a vast area stretching from the Hindu Kush to eastern Anatolia and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf. From their homelands near the Aral sea, the Seljuqs advanced first into Khorasan and then into mainland Persia before eventually conquering eastern Anatolia.

The Seljuq/Seljuk empire was founded by Tughril Beg (1016-1063) in 1037. Tughril was raised by his grandfather, Seljuk-Beg, who was in a high position in the Oghuz Yabgu State. Seljuk gave his name to both the Seljuk empire and the Seljuk dynasty. The Seljuqs united the fractured political scene of the eastern Islamic world and played a key role in the first and second crusades. Highly Persianized in culture and language, the Seljuqs also played an important role in the development of the Turko-Persian tradition, even exporting Persian culture to Anatolia. The settlement of Turkic tribes in the northwestern peripheral parts of the empire, for the strategic military purpose of fending off invasions from neighboring states, led to the progressive Turkicization of those areas.

The apical ancestor of the Seljuqs was their beg, Seljuq, who was reputed to have served in the Khazar army, under whom, circa 950, they migrated to Khwarezm, near the city of Jend, where they converted to Islam.

The Seljuqs were allied with the Persian Samanid shahs against the Qarakhanids. The Samanid fell to the Qarakhanids in Transoxania (992–999), however, whereafter the Ghaznavids arose. The Seljuqs became involved in this power struggle in the region before establishing their own independent base.

Tuğrul and Çağrı Bey

Tughril was the grandson of Seljuq and brother of Chaghri, under whom the Seljuks wrested an empire from the Ghaznavids. Initially the Seljuqs were repulsed by Mahmud and retired to Khwarezm, but Tughril and Chaghri led them to capture Merv and Nishapur (1037). Later they repeatedly raided and traded territory with his successors across Khorasan and Balkh and even sacked Ghazni in 1037. In 1040 at the Battle of Dandanaqan, they decisively defeated Mas’ud I of the Ghaznavids, forcing him to abandon most of his western territories to the Seljuqs. In 1055, Tughril captured Baghdad from the Shi’a Buyids under a commission from the Abbassids.

Alp Arslan

Alp Arslan, the son of Chaghri Beg, expanded significantly upon Tughril’s holdings by adding Armenia and Georgia in 1064 and invading the Byzantine Empire in 1068, from which he annexed almost all of Anatolia. Arslan’s decisive victory at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 effectively neutralized the Byzantine resistance to the Turkish invasion of Anatolia. He authorized his Turkmen generals to carve their own principalities out of formerly Byzantine Anatolia, as atabegs loyal to him. Within two years the Turkmens had established control as far as the Aegean Sea under numerous beghliks (modern Turkish beyliks): the Saltukids in Northeastern Anatolia, Mengujekids in Eastern Anatolia, Artuqids in Southeastern Anatolia, Danishmendis in Central Anatolia, Rum Seljuqs (Beghlik of Suleyman, which later moved to Central Anatolia) in Western Anatolia, and the Beylik of Tzachas of Smyrna in İzmir (Smyrna).

Malik Shah I

Under Alp Arslan‘s successor, Malik Shah, and his two Persian viziers, Nizām al-Mulk and Tāj al-Mulk, the Seljuq state expanded in various directions, to the former Iranian border of the days before the Arab invasion, so that it soon bordered China in the east and the Byzantines in the west. Malikshāh moved the capital from Rey to Isfahan. The Iqta military system and the Nizāmīyyah University at Baghdad were established by Nizām al-Mulk, and the reign of Malikshāh was reckoned the golden age of “Great Seljuq”. The Abbasid Caliph titled him “The Sultan of the East and West” in 1087. The Assassins (Hashshashin) of Hassan-i Sabāh started to become a force during his era, however, and they assassinated many leading figures in his administration; according to many sources these victims included Nizām al-Mulk.

When Malikshāh I died in 1092, the empire split as his brother and four sons quarrelled over the apportioning of the empire among themselves. Malikshāh I was succeeded in Anatolia by Kilij Arslan I, who founded the Sultanate of Rum, and in Syria by his brother Tutush I. In Persia he was succeeded by his son Mahmud I, whose reign was contested by his other three brothers Barkiyaruq in Iraq, Muhammad I in Baghdad, and Ahmad Sanjar in Khorasan. When Tutush I died, his sons Radwan and Duqaq inherited Aleppo and Damascus respectively and contested with each other as well, further dividing Syria amongst emirs antagonistic towards each other.

In 1118, the third son Ahmad Sanjar took over the empire. His nephew, the son of Muhammad I, did not recognize his claim to the throne, and Mahmud II proclaimed himself Sultan and established a capital in Baghdad, until 1131 when he was finally officially deposed by Ahmad Sanjar.

Elsewhere in nominal Seljuq territory were the Artuqids in northeastern Syria and northern Mesopotamia; they controlled Jerusalem until 1098. The Dānišmand dynasty founded a state in eastern Anatolia and northern Syria and contested land with the Sultanate of Rum, and Kerbogha exercised independence as the atabeg of Mosul.

During the First Crusade, the fractured states of the Seljuqs were generally more concerned with consolidating their own territories and gaining control of their neighbours than with cooperating against the crusaders. The Seljuqs easily defeated the untrained People’s Crusade arriving in 1096, but they could not stop the progress of the army of the subsequent Princes’ Crusade, which took important cities such as Nicaea (İznik), Iconium (Konya), Caesarea Mazaca (Kayseri), and Antioch (Antakya) on its march to Jerusalem (Al-Quds). In 1099 the crusaders finally captured the Holy Land and set up the first Crusader states. The Seljuqs had already lost Palestine to the Fatimids, who had recaptured it just before its capture by the crusaders.

During this time conflict with the Crusader states was also intermittent, and after the First Crusade increasingly independent atabegs would frequently ally with the Crusader states against other atabegs as they vied with each other for territory. At Mosul, Zengi succeeded Kerbogha as atabeg and successfully began the process of consolidating the atabegs of Syria. In 1144 Zengi captured Edessa, as the County of Edessa had allied itself with the Ortoqids against him. This event triggered the launch of the Second Crusade. Nur ad-Din, one of Zengi’s sons who succeeded him as atabeg of Aleppo, created an alliance in the region to oppose the Second Crusade, which landed in 1147.

Ahmad Sanjar had to contend with the revolts of Qarakhanids in Transoxiana, Ghorids in Afghanistan and Qarluks in modern Kyrghyzstan, as well as the nomadic Kara-Khitais who invaded the East and captured the Eastern Qarakhanid state. The Kara-Khitais then defeated the Western Qarakhanids, a vassal of the Seljuqs at Khujand. The Qarakhanids turned to their overlord the Seljuqs for help, but at the Battle of Qatwan in 1141, Sanjar was decisively defeated. The Seljuq army suffered great losses and Sanjar barely escaped with his life. The prestige of the Seljuqs became greatly diminished, and they lost all his eastern provinces up to the Syr Darya, with the vassalage of Western Kara-Khanid taken by the Kara-Khitan.

In 1153, the Ghuzz (Oghuz Turks) rebelled and captured Sanjar. He managed to escape after three years but died a year later. Despite several attempts to reunite the Seljuks by his successors, the Crusades prevented them from regaining their former empire. The atabegs, such as Zengids and Artuqids, were only nominally under the Seljuk Sultan, and generally controlled Syria independently. When Ahmed Sanjar died in 1156, it fractured the empire even further and rendered the atabegs effectively independent.

After the Second Crusade, Nur ad-Din’s general Shirkuh, who had established himself in Egypt on Fatimid land, was succeeded by Saladin. In time, Saladin rebelled against Nur ad-Din, and, upon his death, Saladin married his widow and captured most of Syria and created the Ayyubid dynasty.

On other fronts, the Kingdom of Georgia began to become a regional power and extended its borders at the expense of Great Seljuk. The same was true during the revival of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia under Leo II of Armenia in Anatolia. The Abbassid caliph An-Nasir also began to reassert the authority of the caliph and allied himself with the Khwarezmshah Takash.

For a brief period, Togrul III was the Sultan of all Seljuq except for Anatolia. In 1194, however, Togrul was defeated by Takash, the Shah of Khwarezmid Empire, and the Seljuq finally collapsed. Of the former Seljuq Empire, only the Sultanate of Rûm in Anatolia remained. As the dynasty declined in the middle of the thirteenth century, the Mongols invaded Anatolia in the 1260s and divided it into small emirates called the Anatolian beyliks. Eventually one of these, the Ottoman, would rise to power and conquer the rest.

Khwarazmian Empire

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khwarezmshah

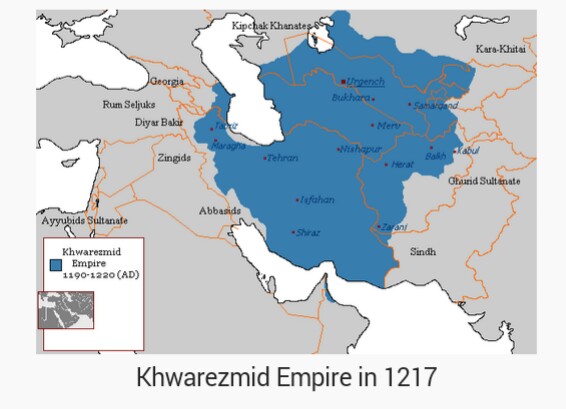

The Khwarazmian dynasty (IPA: [kwəˈrazmēən] or IPA: [kwäˈ-]; also known as the Khwarezmid dynasty, dynasty of Khwarazm Shahs, and other spelling variants; from Persian خوارزمشاهیان Khwārazmshāhiyān, “Kings of Khwarezmia“) was a Persianate Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin.

The dynasty ruled large parts of Greater Iran during the High Middle Ages, in the approximate period of 1077 to 1231, first as vassals of the Seljuqs and Kara-Khitan, and later as independent rulers, up until the Mongol invasion of Khwarezmia in the 13th century. The dynasty was founded by Anush Tigin Gharchai, a former Turkish slave of the Seljuq sultans, who was appointed the governor of Khwarezm. His son, Qutb ad-Din Muhammad I, became the first hereditary Shah of Khwarezm.

The date of the founding of the Khwarazmian dynasty remains debatable. During a revolt in 1017, Khwarezmian rebels murdered Abu’l-Abbas Ma’mun and his wife, Hurra-ji, sister of the Ghaznavid sultan Mahmud. In response, Mahmud invaded and occupied the region of Khwarezm, which included Nasa and the ribat of Farawa. As a result, Khwarezm became a province of the Ghaznavid Empire from 1017 to 1034. In 1077 the governorship of the province, which since 1042/1043 belonged to the Seljuqs, fell into the hands of Anush Tigin Gharchai, a former Turkic slave of the Seljuq sultan. In 1141, the Seljuq Sultan Ahmed Sanjar was defeated by the Kara Khitay at the battle of Qatwan, and Anush Tigin’s grandson Ala ad-Din Atsiz became a vassal to Yelü Dashi of the Kara Khitan.

Sultan Ahmed Sanjar died in 1156. As the Seljuk state fell into chaos, the Khwarezm-Shahs expanded their territories southward. In 1194, the last Sultan of the Great Seljuq Empire, Toghril III, was defeated and killed by the Khwarezm ruler Ala ad-Din Tekish, who conquered parts of Khorasan and western Iran. In 1200, Tekish died and was succeeded by his son, Ala ad-Din Muhammad, who initiated a conflict with the Ghurids and was defeated by them at Amu Darya (1204). Following the sack of Khwarizm, Muhammad appealed for aid from his suzerain, the Kara Khitai who sent him an army. With this reinforcement, Muhammad won a victory over the Ghorids at Hezarasp (1204) and forced them out of Khwarizm. Muhammad’s gratitude towards his suzerain was short-lived. He again initiated a conflict, this time with the aid of the Kara-Khanids, and defeated a Kara-Khitai army at Talas (1210), but allowed Samarkand (1210) to be occupied by the Kara-Khitai. He overthrew the Karakhanids (1212) and Ghurids (1215). In 1212, Muhammad II shifted capital from Gurganj to Samarkand. Thus Muhammad II incorporated nearly the whole of Transoxania and present-day Afghanistan into his empire, which after further conquests in western Persia (by 1217) stretched from the Syr Darya to the Zagros Mountains, and from the Indus Valley to the Caspian Sea.

In 1218, Genghis Khan sent a trade mission to the state, but at the town of Otrar the governor, suspecting the Khan’s ambassadors to be spies, confiscated their goods and executed them. Genghis Khan demanded reparations, which the Shah refused to pay. Genghis retaliated with a force of 200,000 men, launching a multi-pronged invasion. In February 1220 the Mongolian army crossed the Syr Darya, beginning the Mongol invasion of Central Asia. The Mongols stormed Bukhara, Gurganj and the Khwarezmid capital Samarkand. The Shah fled and died some weeks later on an island in the Caspian Sea.

In Great Captains Unveiled of 1927, B.H. Liddell Hart gave details of the Mongol campaign against Khwarezm, underscoring his own philosophy of “the indirect approach,” and highlighting many of the tactics used by Genghis which were to be subsequently included in the Blitzkrieg tactics employed less than two decades later by Nazi Germany.

The son of Ala ad-Din Muhammad, Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu became the new Sultan (he rejected the title Shah). He attempted to flee to India, but the Mongols caught up with him before he got there, and he was defeated at the Battle of Indus. He escaped and sought asylum in the Sultanate of Delhi. Iltumish however denied this to him in deference to the relationship with the Abbasid caliphs. Returning to Persia, he gathered an army and re-established a kingdom. He never consolidated his power, however, spending the rest of his days struggling against the Mongols, the Seljuks of Rum, and pretenders to his own throne. He lost his power over Persia in a battle against the Mongols in the Alborz Mountains. Escaping to the Caucasus, he captured Azerbaijan in 1225, setting up his capital at Tabriz. In 1226 he attacked Georgia and sacked Tbilisi. Following on through the Armenian highlands he clashed with the Ayyubids, capturing the town Ahlat along the western shores of the Lake Van, who sought the aid of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm. Sultan Kayqubad I defeated him at Arzinjan on the Upper Euphrates at the Battle of Yassıçemen in 1230. He escaped to Diyarbakir, while the Mongols conquered Azerbaijan in the ensuing confusion. He was murdered in 1231 by Kurdish highwaymen.

Sultanate of Rum

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sultanate_of_R%C3%BBm

The Sultanate of Rum (Turkish: Anadolu Selçuklu Devleti, meaning “Anatolian Seljuk State”; Persian: سلجوقیان روم Saljūqiyān-i Rūm) was a medieval Turko-Persian, Sunni Muslim state in Anatolia. It existed from 1077 to 1307, with capitals first at İznik and then at Konya. However, the court of the sultanate was highly mobile, and cities like Kayseri and Sivas also temporarily functioned as capitals. At its height, the sultanate stretched across central Anatolia, from the shoreline of Antalya and Alanya on the Mediterranean coast to the territory of Sinop on the Black Sea. In the east, the sultanate absorbed other Turkish states and reached Lake Van. Its westernmost limit was near Denizli and the gates of the Aegean basin.

The term “Rûm” comes from the Persian word for the Roman Empire. The Seljuqs called the lands of their sultanate Rum because it had been established on territory long considered “Roman”, i.e. Byzantine, by Muslim armies. The state is occasionally called the Sultanate of Konya (or Sultanate of Iconium) in older Western sources.

The sultanate prospered, particularly during the late 12th and early 13th centuries when it took from the Byzantines key ports on the Mediterranean and Black Sea coasts. Within Anatolia the Seljuqs fostered trade through a program of caravanserai-building, which facilitated the flow of goods from Iran and Central Asia to the ports. Especially strong trade ties with the Genoese formed during this period. The increased wealth allowed the sultanate to absorb other Turkish states that had been established in eastern Anatolia after the Battle of Manzikert: the Danishmends, the Mengücek, the Saltukids, and the Artuqids. Seljuq sultans successfully bore the brunt of the Crusades but in 1243 succumbed to the advancing Mongols. The Seljuqs became vassals of the Mongols, following the battle of Kose Dag, and despite the efforts of shrewd administrators to preserve the state’s integrity, the power of the sultanate disintegrated during the second half of the 13th century and had disappeared completely by the first decade of the 14th.

In its final decades, a number of small principalities, or beyliks, emerged and rose to dominance in the territory of the Sultanate, including that of the House of Osman, which later founded the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottoman Empire

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_Empire

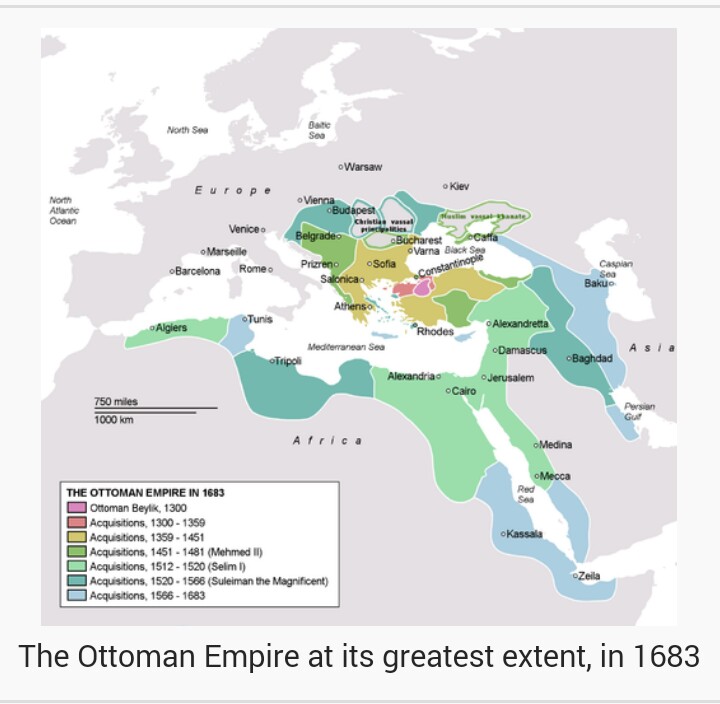

The Ottoman Empire (/ˈɒtəmən/; Ottoman Turkish: دَوْلَتِ عَلِيّهٔ عُثمَانِیّه, Devlet-i Aliyye-i Osmâniyye, Modern Turkish: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu or Osmanlı Devleti), also historically referred to as the Turkish Empire or Turkey, was a Sunni Islamic state founded by Oghuz Turks under Osman I in northwestern Anatolia in 1299. With conquests in the Balkans by Murad I between 1362 and 1389, and the conquest of Constantinople by Mehmed II in 1453, the Ottoman sultanate was transformed into an empire.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, in particular at the height of its power under the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Empire was a powerful multinational, multilingual empire controlling much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia, the Caucasus, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa. At the beginning of the 17th century the empire contained 32 provinces and numerous vassal states. Some of these were later absorbed into the empire, while others were granted various types of autonomy during the course of centuries.

With Constantinople as its capital and control of lands around the Mediterranean basin, the Ottoman Empire was at the centre of interactions between the Eastern and Western worlds for six centuries. Following a long period of military setbacks against European powers and gradual decline, the empire collapsed and was dissolved in the aftermath of World War I, leading to the emergence of the new state of Turkey in the Ottoman Anatolian heartland, as well as the creation of modern Balkan and Middle Eastern states.

The word “Ottoman” is a historical anglicisation of the name of Osman I, the founder of the Empire and of the ruling House of Osman (also known as the Ottoman dynasty). Osman’s name in turn was derived from the Persian form of the name ʿUṯmān عثمان of ultimately Arabic origin. In Ottoman Turkish, the empire was referred to as Devlet-i ʿAliyye-yi ʿOsmâniyye (دَوْلَتِ عَلِيّهٔ عُثمَانِیّه), or alternatively Osmanlı Devleti (عثمانلى دولتى). In Modern Turkish, it is known asOsmanlı İmparatorluğu (“Ottoman Empire”) orOsmanlı Devleti (“The Ottoman State”).

In the West, the two names “Ottoman Empire” and “Turkey” were often used interchangeably, with “Turkey” being increasingly favored both in formal and informal situations. This dichotomy was officially ended in 1920–23 when the newly established Ankara-based Turkish government chose Turkey as the sole official name.

Ertuğrul, father of Osman I, founder of the Ottoman Empire, arrived in Anatolia from Merv (Turkmenistan) with 400 horsemen to aid the Seljuks of Rum against the Byzantines. After the demise of the Turkish Seljuk Sultanate of Rum in the 14th century, Anatolia was divided into a patchwork of independent, mostly Turkish states, the so-called Ghazi emirates. One of the emirates was led by Osman I (1258–1326), from whom the name Ottoman is derived. Osman I extended the frontiers of Turkish settlement toward the edge of the Byzantine Empire. It is not well understood how the Osmanli came to dominate their neighbours, as the history of medieval Anatolia is still little known.

In the century after the death of Osman I, Ottoman rule began to extend over the Eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans. Osman’s son, Orhan, captured the city of Bursa in 1324 and made it the new capital of the Ottoman state. The fall of Bursa meant the loss of Byzantine control over northwestern Anatolia. The important city of Thessaloniki was captured from the Venetians in 1387. The Ottoman victory at Kosovo in 1389 effectively marked the end of Serbian power in the region, paving the way for Ottoman expansion into Europe. The Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, widely regarded as the last large-scale crusade of the Middle Ages, failed to stop the advance of the victorious Ottoman Turks.

With the extension of Turkish dominion into the Balkans, the strategic conquest of Constantinople became a crucial objective. The empire controlled nearly all former Byzantine lands surrounding the city, but the Byzantines were temporarily relieved when the Turkish-Mongolian leader Timur invaded Anatolia from the east. In the Battle of Ankara in 1402, Timur defeated the Ottoman forces and took Sultan Bayezid I as a prisoner, throwing the empire into disorder. The ensuing civil war lasted from 1402 to 1413 as Bayezid’s sons fought over succession. It ended when Mehmet I emerged as the sultan and restored Ottoman power, bringing an end to the Interregnum, also known as the Fetret Devri.

Part of the Ottoman territories in the Balkans (such as Thessaloniki, Macedonia and Kosovo) were temporarily lost after 1402 but were later recovered by Murad II between the 1430s and 1450s. On 10 November 1444, Murad II defeated the Hungarian, Polish, and Wallachian armies under Władysław III of Poland (also King of Hungary) and János Hunyadi at the Battle of Varna, the final battle of the Crusade of Varna, although Albanians under Skanderbeg continued to resist. Four years later, János Hunyadi prepared another army (of Hungarian and Wallachian forces) to attack the Turks but was again defeated by Murad II at the Second Battle of Kosovo in 1448.

The son of Murad II, Mehmed II, reorganized the state and the military, and conquered Constantinople on 29 May 1453. Mehmed allowed the Orthodox Church to maintain its autonomy and land in exchange for accepting Ottoman authority. Because of bad relations between the states of western Europe and the later Byzantine Empire, the majority of the Orthodox population accepted Ottoman rule as preferable to Venetian rule. Albanian resistance was a major obstacle to Ottoman expansion on the Italian peninsula.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ottoman Empire entered a period of expansion. The Empire prospered under the rule of a line of committed and effective Sultans. It also flourished economically due to its control of the major overland trade routes between Europe and Asia.

Sultan Selim I (1512–1520) dramatically expanded the Empire’s eastern and southern frontiers by defeating Shah Ismail of Safavid Persia, in the Battle of Chaldiran. Selim I established Ottoman rule in Egypt, and created a naval presence on the Red Sea. After this Ottoman expansion, a competition started between the Portuguese Empire and the Ottoman Empire to become the dominant power in the region.

Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566) captured Belgrade in 1521, conquered the southern and central parts of the Kingdom of Hungary as part of the Ottoman–Hungarian Wars, and, after his historical victory in the Battle of Mohács in 1526, he established Turkish rule in the territory of present-day Hungary (except the western part) and other Central European territories. He then laid siege to Vienna in 1529, but failed to take the city. In 1532, he made another attack on Vienna, but was repulsed in the Siege of Güns. Transylvania, Wallachia and, intermittently, Moldavia, became tributary principalities of the Ottoman Empire. In the east, the Ottoman Turks took Baghdad from the Persians in 1535, gaining control of Mesopotamia and naval access to the Persian Gulf.

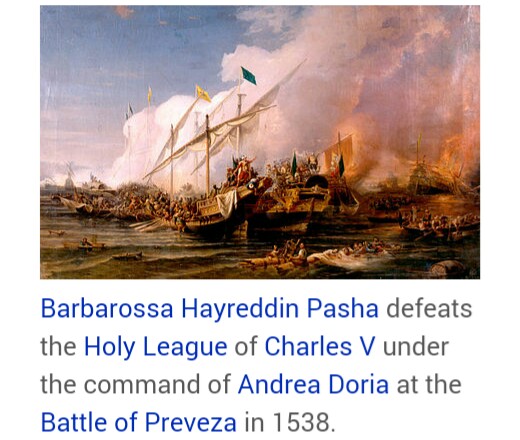

France and the Ottoman Empire, united by mutual opposition to Habsburg rule, became strong allies. The French conquests of Nice (1543) and Corsica (1553) occurred as a joint venture between the forces of the French king Francis I and Suleiman, and were commanded by the Ottoman admirals Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha and Turgut Reis. A month prior to the siege of Nice, France supported the Ottomans with an artillery unit during the Ottoman conquest of Esztergom in 1543. After further advances by the Turks in 1543, the Habsburg ruler Ferdinand officially recognized Ottoman ascendancy in Hungary in 1547.

In 1559, after the first Ajuran-Portuguese war the Ottoman Empire would later absorb the weakened Adal Sultanate into its domain. This expansion furthered Ottoman rule in Somalia and the Horn of Africa. This also increased its influence in the Indian Ocean to compete with the Portuguese with its close ally the Ajuran Empire.

By the end of Suleiman’s reign, the Empire’s population totaled about 15,000,000 people extending over three continents. In addition, the Empire became a dominant naval force, controlling much of the Mediterranean Sea. By this time, the Ottoman Empire was a major part of the European political sphere. The success of its political and military establishment has been compared to the Roman Empire, by the likes of Italian scholar Francesco Sansovino and the French political philosopher Jean Bodin.

The stagnation and decline, Stephen Lee argues, was relentless after 1566, interrupted by a few short revivals or reform and recovery. The decline gathered speed so that the Empire in 1699 was, “a mere shadow of that which intimidated East and West alike in 1566.” Although there are dissenting scholars, most historians point to “degenerate Sultans, incompetent Grand Viziers, debilitated and ill-equipped armies, corrupt officials, avaricious speculators, grasping enemies, and treacherous friends.” The main cause was a failure of leadership, as Lee argues the first 10 sultans from 1292 to 1566, with one exception, had done quite well. The next 13 sultans from 1566 to 1703, with two exceptions, were lackadaisical or incompetent rulers, says Lee. In a highly centralized system, the failure at the center proved fatal. A direct result was the strengthening of provincial elites who increasingly ignored Constantinople. Secondly the military strength of European enemies grew stronger and stronger, while the Ottoman armies and arms scarcely improved. Finally the Ottoman economic system grew distorted and impoverished, as war caused inflation, world trade moved in other directions, and the deterioration of law and order made economic progress difficult.

The effective military and bureaucratic structures of the previous century came under strain during a protracted period of misrule by weak Sultans. The Ottomans gradually fell behind the Europeans in military technology as the innovation that fed the Empire’s forceful expansion became stifled by growing religious and intellectual conservatism. But in spite of these difficulties, the Empire remained a major expansionist power until the Battle of Vienna in 1683, which marked the end of Ottoman expansion into Europe.

The discovery of new maritime trade routes by Western European states allowed them to avoid the Ottoman trade monopoly. The Portuguese discovery of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 initiated a series of Ottoman-Portuguese naval wars in the Indian Ocean throughout the 16th century. The Ajuran Empire allied with the Ottomans defied the Portuguese economic monopoly in the Indian Ocean by employing a new coinage which followed the Ottoman pattern, thus proclaiming an attitude of economic independence in regard to the Portuguese.

Under Ivan IV (1533–1584), the Tsardom of Russia expanded into the Volga and Caspian region at the expense of the Tatar khanates. In 1571, the Crimean khan Devlet I Giray, supported by the Ottomans, burned Moscow. The next year, the invasion was repeated but repelled at the Battle of Molodi. The Crimean Khanate continued to invade Eastern Europe in a series of slave raids, and remained a significant power in Eastern Europe until the end of the 17th century.

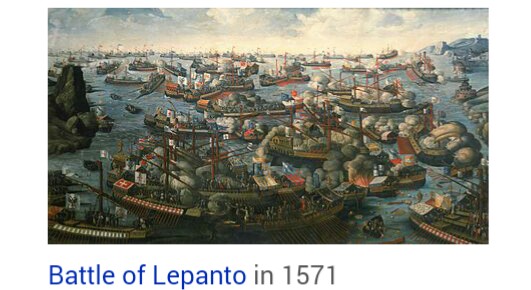

In southern Europe, a Catholic coalition led by Philip II of Spain won a victory over the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto (1571). It was a startling, if mostly symbolic, blow to the image of Ottoman invincibility, an image which the victory of the Knights of Malta against the Ottoman invaders in the 1565 Siege of Malta had recently set in motion eroding. The battle was far more damaging to the Ottoman navy in sapping experienced manpower than the loss of ships, which were rapidly replaced. The Ottoman navy recovered quickly, persuading Venice to sign a peace treaty in 1573, allowing the Ottomans to expand and consolidate their position in North Africa.

By contrast, the Habsburg frontier had settled somewhat, a stalemate caused by a stiffening of the Habsburg defences. The Long War against Habsburg Austria (1593–1606) created the need for greater numbers of infantry equipped with firearms, resulting in a relaxation of recruitment policy. This contributed to problems of indiscipline and outright rebelliousness within the corps, which were never fully solved. Irregular sharpshooters (Sekban) were also recruited, and on demobilization turned to brigandage in the Jelali revolts (1595–1610), which engendered widespread anarchy in Anatolia in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. With the Empire’s population reaching 30,000,000 people by 1600, the shortage of land placed further pressure on the government . In spite of these problems, the Ottoman state remained strong, and its army did not collapse or suffer crushing defeats. The only exception were campaigns against the Safavid dynasty of Persia where many of the Ottoman eastern provinces were lost, some permanently. However, its campaigns became increasingly inconclusive, even against weaker states with much smaller forces such as Poland or Austria.

During his brief majority reign, Murad IV (1612–1640) reasserted central authority and recaptured Iraq (1639) from the Safavids. The Sultanate of women (1648–1656) was a period in which the mothers of young sultans exercised power on behalf of their sons. The most prominent women of this period were Kösem Sultan and her daughter-in-law Turhan Hatice, whose political rivalry culminated in Kösem’s murder in 1651. During the Köprülü Era (1656–1703), effective control of the Empire was exercised by a sequence of Grand Viziers from the Köprülü family. The Köprülü Vizierate saw renewed military success with authority restored inTransylvania, the conquest of Crete completed in 1669 and expansion into Polish southern Ukraine, with the strongholds ofKhotyn and Kamianets-Podilskyi and the territory of Podolia ceding to Ottoman control in 1676

This period of renewed assertiveness came to a calamitous end in May 1683 when Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha led a huge army to attempt a second Ottoman siege of Vienna in the Great Turkish War of 1683–1687. The final assault being fatally delayed, the Ottoman forces were swept away by allied Habsburg, German and Polish forces spearheaded by the Polish king Jan III Sobieski at the Battle of Vienna. The alliance of the Holy League pressed home the advantage of the defeat at Vienna, culminating in the Treaty of Karlowitz (26 January 1699), which ended the Great Turkish War. The Ottomans surrendered control of significant territories, many permanently. Mustafa II (1695–1703) led the counterattack of 1695–96 against the Habsburgs in Hungary, but was undone at the disastrous defeat at Zenta (11 September 1697).

During this period Russian warm seas expansion presented a large and growing threat. Accordingly, King Charles XII of Sweden was welcomed as an ally in the Ottoman Empire following his defeat by the Russians at the Battle of Poltava in 1709 (part of the Great Northern War of 1700–1721.) Charles XII persuaded the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed III to declare war on Russia, which resulted in the Ottoman victory at the Pruth River Campaign of 1710–1711.

After the Austro-Turkish War of 1716–1718 the Treaty of Passarowitz confirmed the loss of the Banat, Serbia and “Little Walachia” (Oltenia) to Austria. The Treaty also revealed that the Ottoman Empire was on the defensive and unlikely to present any further aggression in Europe. The Austro-Russian–Turkish War, which was ended by the Treaty of Belgrade in 1739, resulted in the recovery of Serbia and Oltenia, but the Empire lost the port of Azov to the Russians. After this treaty the Ottoman Empire was able to enjoy a generation of peace, as Austria and Russia were forced to deal with the rise of Prussia.

Educational and technological reforms were made, including the establishment of higher education institutions such as the Istanbul Technical University. In 1734 an artillery school was established to impart Western-style artillery methods, but the Islamic clergy successfully objected under the grounds of theodicy. In 1754 the artillery school was reopened on a semi-secret basis. In 1726, Ibrahim Muteferrika convinced the Grand Vizier Nevşehirli Damat İbrahim Pasha, the Grand Mufti, and the clergy on the efficiency of the printing press, and Muteferrika was later granted by Sultan Ahmed III permission to publish non-religious books (despite opposition from some calligraphers and religious leaders). Muteferrika’s press published its first book in 1729 and, by 1743, issued 17 works in 23 volumes, each having between 500 and 1,000 copies.

In 1768 Russian-backed Ukrainian Haidamaks, pursuing Polish confederates, entered Balta, an Ottoman-controlled town on the border of Bessarabia, and massacred its citizens and burned the town to the ground. This action provoked the Ottoman Empire into the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca of 1774 ended the war and provided freedom to worship for the Christian citizens of the Ottoman-controlled provinces of Wallachia and Moldavia. By the late 18th century, a number of defeats in several wars with Russia led some people in the Ottoman Empire to conclude that the reforms of Peter the Great had given the Russians an edge, and the Ottomans would have to keep up with Western technology in order to avoid further defeats.

Selim III (1789–1807) made the first major attempts to modernize the army, but reforms were hampered by the religious leadership and the Janissary corps. Jealous of their privileges and firmly opposed to change, the Janissary created a revolt. Selim’s efforts cost him his throne and his life, but were resolved in spectacular and bloody fashion by his successor, the dynamic Mahmud II, who xeliminated the Janissary corps in 1826.

The Serbian revolution (1804–1815) marked the beginning of an era of national awakening in the Balkans during the Eastern Question. Suzerainty of Serbia as a hereditary monarchy under its own dynasty was acknowledged de jure in 1830. In 1821, the Greeks declared war on the Sultan. A rebellion that originated in Moldavia as a diversion was followed by the main revolution in the Peloponnese, which, along with the northern part of the Gulf of Corinth, became the first parts of the Ottoman Empire to achieve independence (in 1829). By the mid-19th century, the Ottoman Empire was called the “sick man” by Europeans. The suzerain states – the Principality of Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia and Montenegro – moved towards de jure independence during the 1860s and 1870s.

During the Tanzimat period (1839–1876), the government’s series of constitutional reforms led to a fairly modern conscripted army, banking system reforms, the decriminalization of homosexuality, the replacement of religious law with secular law and guilds with modern factories. The Ottoman Ministry of Post was established in Istanbul on 23 October 1840.

Samuel Morse received a patent for the telegraph in 1847, which was issued by Sultan Abdülmecid who personally tested the new invention. Following this successful test, installation works of the first Turkish telegraph line (Istanbul-Edirne–Şumnu) began on 9 August 1847. The reformist period peaked with the Constitution, called the Kanûn-u Esâsî. The empire’s First Constitutional era was short-lived. The parliament survived for only two years before the sultan suspended it.

The Christian population of the empire, owing to their higher educational levels, started to pull ahead of the Muslim majority, leading to much resentment on the part of the latter. In 1861, there were 571 primary and 94 secondary schools for Ottoman Christians with 140,000 pupils in total, a figure that vastly exceeded the number of Muslim children in school at the same time, who were further hindered by the amount of time spent learning Arabic and Islamic theology. In turn, the higher educational levels of the Christians allowed them to play a large role in the economy. In 1911, of the 654 wholesale companies in Istanbul, 528 were owned by ethnic Greeks.

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was part of a long-running contest between the major European powers for influence over territories of the declining Ottoman Empire. The financial burden of the war led the Ottoman state to issue foreign loans amounting to 5 million pounds sterling on 4 August 1854. The war caused an exodus of the Crimean Tatars, about 200,000 of whom moved to the Ottoman Empire in continuing waves of emigration. Toward the end of the Caucasian Wars, 90% of the Circassians were ethnically cleansed and exiled from their homelands in the Caucasus and fled to the Ottoman Empire, resulting in the settlement of 500,000 to 700,000 Circassians in Turkey. Some Circassian organisations give much higher numbers, totaling 1–1.5 million deported and/or killed.

The Ottoman bashi-bazouks brutally suppressed the Bulgarian uprising of 1876, massacring up to 100,000 people in the process. The Russo-Turkish War (1877–78) ended with a decisive victory for Russia. As a result, Ottoman holdings in Europe declined sharply; Bulgaria was established as an independent principality inside the Ottoman Empire, Romania achieved full independence. Serbia and Montenegro finally gained complete independence, but with smaller territories. In 1878, Austria-Hungary unilaterally occupied the Ottoman provinces of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Novi Pazar. Although the Ottoman government contested this move its troops were defeated within three weeks.

In return for British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli‘s advocacy for restoring the Ottoman territories on the Balkan Peninsula during the Congress of Berlin, Britain assumed the administration of Cyprus in 1878, and later sent troops to Egypt in 1882, with the pretext of helping the Ottoman government to put down the Urabi Revolt, effectively gaining control in both territories.

From 1894 to 1896, between 100,000 and 300,000 Armenians living throughout the empire were killed in what became known as the Hamidian massacres.

As the Ottoman Empire gradually shrank in size, many Balkan Muslims migrated to the empire’s remaining territory in Balkans or to the heartland in Anatolia. By 1923, only Anatolia and eastern Thrace remained as the Muslim land.

The Second Constitutional Era began after the Young Turk Revolution (3 July 1908) with the sultan’s announcement of the restoration of the 1876 constitution and the reconvening of the Ottoman parliament. Although it began a series of massive political and military reform over the next six years, it marked the beginning of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. This era is dominated by the politics of the Committee of Union and Progress, and the movement that would become known as the Young Turks.

Profiting from the civil strife, Austria-Hungary officially annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908, but it pulled its troops out of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, another contested region between the Austrians and Ottomans, to avoid a war. During the Italo-Turkish War(1911–12) in which the Ottoman Empire lost Libya, the Balkan League declared war against the Ottoman Empire. The Empire lost the Balkan Wars (1912–13). It lost its Balkan territories except East Thrace and the historic Ottoman capital city of Edirne during the war. Fearing religious persecution, around 400,000 Muslims fled to present-day Turkey. Due to a cholera epidemic, many did not survive the journey. According to the estimates of Justin McCarthy, during the period from 1821 to 1922 alone, the ethnic cleansing of Ottoman Muslims in the Balkans led to the death of several million individuals and the expulsion of a similar number. By 1914, the Ottoman Empire had been driven out of nearly all of Europe and North Africa. It still controlled 28 million people, of whom 15.5 million were in modern-day Turkey, 4.5 million in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan, and 2.5 million in Iraq. Another 5.5 million people were under nominal Ottoman rule in the Arabian peninsula.

In November 1914, the Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers, in which it took part in the Middle Eastern theatre. There were several important Ottoman victories in the early years of the war, such as the Battle of Gallipoli and the Siege of Kut, but there were setbacks as well, such as the disastrous Caucasus Campaign against the Russians. The United States never declared war against the Ottoman Empire.

In 1915, as the Russian Caucasus Army continued to advance into eastern Anatolia, the Ottoman government started the deportation of its ethnic Armenian population, resulting in the death of approximately 1.5 million Armenians in what became known as the Armenian Genocide. Large-scale massacres were also committed against the Empire’s Greek and Assyrian minorities as part of the same campaign of ethnic cleansing.

The Arab Revolt which began in 1916 turned the tide against the Ottomans at the Middle Eastern front, where they initially seemed to have the upper hand during the first two years of the war. The Armistice of Mudros, signed on 30 October 1918, ended the hostilities in the Middle Eastern theatre, and was followed with occupation of Constantinople and subsequent partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. Under the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres, the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire was solidified. The last quarter of the 19th and the early part of the 20th century saw some 7–9 million Turkish-Muslim refugees from the lost territories of the Caucasus, Crimea, Balkans, and the Mediterranean islands migrate to Anatolia and Eastern Thrace.

The occupation of Constantinople and İzmir led to the establishment of a Turkish national movement, which won the Turkish War of Independence (1919–22) under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal (later given the surname “Atatürk”). The sultanate was abolished on 1 November 1922, and the last sultan, Mehmed VI (reigned 1918–22), left the country on 17 November 1922. The Grand National Assembly of Turkey declared the Republic of Turkey on 29 October 1923. The caliphate was abolished on 3 March 1924.