The Portuguese Empire was the longest-lived of the modern European colonial empires, spanning almost 600 years, from the capture of Ceuta in 1415 to the handover of Macau to the People’s Republic of China in 1999 (de facto) or the granting of sovereignty to East Timor in 2002 (de jure) after occupation by Indonesia since 1975. The empire spread throughout a vast number of territories that are now part of 53 different sovereign states, leaving a profound cultural and architectural influence across the globe with a legacy of over 250 million Portuguese speakers today (making it the sixth most spoken first language) and a number of Portuguese-based creoles.

By 1139, Portugal established itself as a kingdom independent from León. In the 15th and 16th centuries, as the result of pioneering the Age of Discovery, Portugal expanded western influence and established the first global empire, becoming one of the world’s major economic, political and military powers, and ultimately dividing the world with Spain.

The land within the borders of the current Portuguese Republic has been continually fought over and settled since prehistoric times. The Celts and the Romans were followed by the Visigothic and the Suebi Germanic peoples, who were themselves later invaded by the Moors. These Muslim peoples were eventually expelled during the Christian Reconquista of the peninsula.

The early history of Portugal is shared with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula located in South Western Europe. The name of Portugal derives from the Roman name Portus Cale. The region was settled by Pre-Celts and Celts, giving origin to peoples like the Gallaeci, Lusitanians, Celtici and Cynetes, visited by Phoenicians and Carthaginians, incorporated in the Roman Republic dominions as Lusitania and part of Gallaecia, after 45 BC until 298 AD, settled again by Suebi, Buri, and Visigoths, and conquered by Moors. Other influences include some 5th century vestiges of Alan settlement, which were found in Alenquer (old Germanic “Alankerk” ), Coimbra and Lisbon.

It is believed by some scholars that early in the first millennium BC, several waves of Celts invaded Portugal from Central Europe and inter-married with the local populations, forming different ethnic groups, with many tribes.

Chief among these tribes were the Calaicians or Gallaeci of Northern Portugal, the Lusitanians of central Portugal, the Celtici of Alentejo, and the Cynetes or Conii of the Algarve. Among the lesser tribes or sub-divisions were the Bracari, Coelerni, Equaesi, Grovii, Interamici, Leuni, Luanqui, Limic, Narbasi, Nemetati, Paesuri, Quaquerni, Seurbi, Tamagani, Tapoli, Turduli, Turduli Veteres, Turdulorum Oppida, Turodi, and Zoelae.

There were in the southern part of the country some small, semi-permanent commercial coastal settlements founded by Phoenicians–Carthaginians (such as Tavira, in the Algarve).

Roman Lusitania and Gallaecia

Romans first invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 219 BC. By 19 BC, almost the entire peninsula had been annexed to the Roman Republic. The Carthaginians, Rome’s adversary in the Punic Wars, were expelled from their coastal colonies.

The Roman conquest of what is now part of modern day Portugal took almost two hundred years and took many lives of young soldiers and the lives of those who were sentenced to a certain death in the slavery mines when not sold as slaves to other parts of the empire. It suffered a severe setback in 150 BC, when a rebellion began in the north. The Lusitanians and other native tribes, under the leadership of Viriathus, wrested control of all of western Iberia.

Rome sent numerous legions and its best generals to Lusitania to quell the rebellion, but to no avail — the Lusitanians kept conquering territory. The Roman leaders decided to change their strategy. They bribed Viriathus’s allies to kill him. In 139 BC, Viriathus was assassinated, and Tautalus became leader.

Rome installed a colonial regime. The complete Romanization of Lusitania only took place in the Visigothic era.

In 27 BC, Lusitania gained the status of Roman province. Later, a northern province of Lusitania was formed, known as Gallaecia, with capital in Bracara Augusta, today’s Braga. There are still many ruins of castros (hill forts) all over modern Portugal and remains of Castro culture. Numerous Roman sites are scattered around present-day Portugal, some urban remains are quite large, like Conimbriga and Mirobriga.

In the early 5th century, Germanic tribes, namely the Suebi and the Vandals (Silingi and Hasdingi) together with their allies, the Sarmatians and Alans invaded the Iberian Peninsula where they would form their kingdom. The Kingdom of the Suebi was the Germanic post-Roman kingdom, established in the former Roman provinces of Gallaecia and Lusitania.

About 410 and during the 6th century it became a formally declared kingdom, where king Hermeric made a peace treaty with the Gallaecians before passing his domains to Rechila, his son. In 448 Réchila died, leaving the state in expansion to Rechiar.

In the year 500, the Visigothic Kingdom was installed in Iberia, centred on Toledo. The Visigoths eventually conquered the Suebi and its capital city Bracara (modern day Portugal’s Braga) in 584–585. It maintained its independence until 585, when it was annexed by the Visigoths, and turned into the sixth province of the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania.

For the next 300 years and by the year 700, the entire Iberian Peninsula was ruled by Visigoths, having survived until 711, when King Roderic (Rodrigo) was killed while opposing an invasion from the south by the Umayyad Muslims.

Moorish Iberia

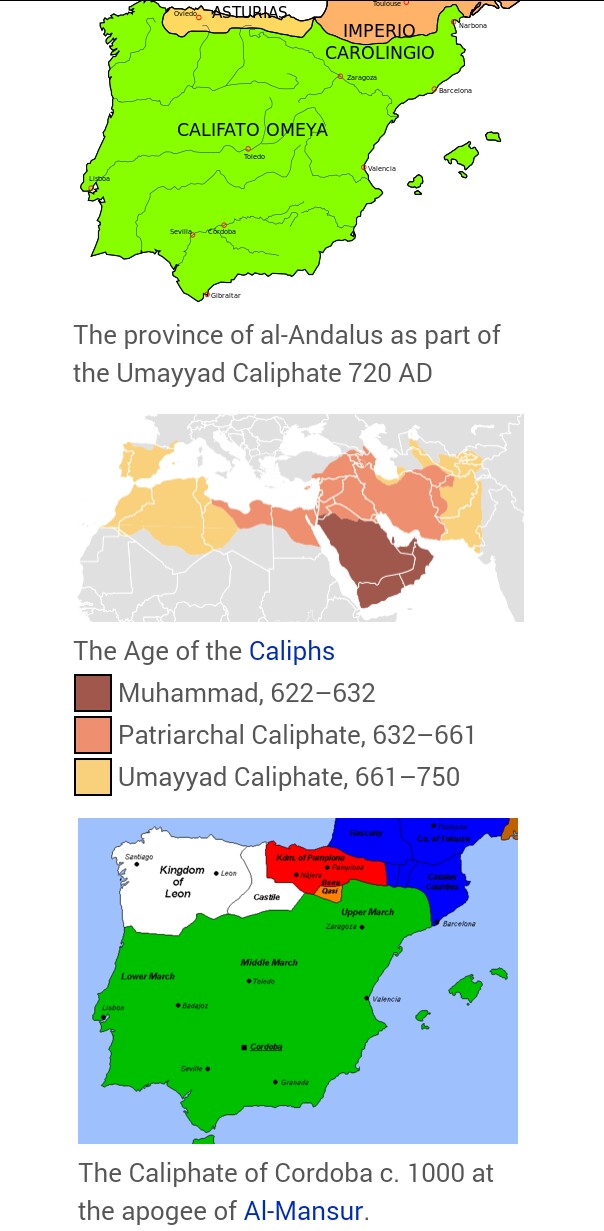

Today’s modern day continental Portugal, along with a significant part of Spain, was part of the Umayyad Caliphate for approximately five centuries (711 AD – 1249 AD), following the Umayyad Caliphate conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in 711 AD.

After defeating the Visigoths in only a few months, the Umayyad Caliphate started expanding rapidly in the peninsula. Beginning in 711, the land that is now Portugal became part of the vast Umayyad Caliphate’s empire of Damascus. which stretched from the Indus river in Pakistan up to the South of France, until its collapse in 750, a year in which the west of the empire gained its independence under Abd-ar-Rahman I with the creation of the Emirate of Córdoba. After almost two centuries, the Emirate became the Caliphate of Córdoba in 929, until its dissolution a century later in 1031 into no less than 23 small kingdoms, called Taifa kingdoms.

The governors of the taifas each proclaimed themselves Emir of their provinces and established diplomatic relations with the Christian kingdoms of the north. Most of Portugal fell into the hands of the Taifa of Badajoz of the Aftasid Dynasty, and after a short spell of an ephemeral Taifa of Lisbon in 1022, fell under the dominion of the Taifa of Seville of the Abbadids poets. The Taifa period ended with the conquest of the Almoravids who came from Morocco in 1086 winning a decisive victory at the Battle of Sagrajas, followed a century later in 1147, after the second period of Taifa, by the Almohads, also from Marrakesh.

Al-Andalus was divided into different districts called Kura. Gharb Al-Andalus at its largest was constituted of ten kuras, each with a distinct capital and governor. The main cities of the period in Portugal were Beja, Silves, Alcácer do Sal, Santarém and Lisbon.

The Muslim population of the region consisted mainly of native Iberian converts to Islam (the so-called Muwallad or Muladi) and to a lesser extent Berbers and Arabs. The Arabs were principally noblemen from Oman; and though few in numbers, they constituted the elite of the population. The Berbers were originally from the Atlas mountains and Rif mountains of North Africa and were essentially nomads. In Portugal, the Muslim population (or “Moors“), relatively small in numbers, stayed in the Algarve region, and south of the Tagus. Today, there are approximately 800 words in the Portuguese language of Arabic origin. The Muslims were expelled from Portugal 300 years earlier than in neighbouring Spain, which is reflected both in Portuguese culture and the language, which is mostly Celtiberian and Vulgar Latin.

Reconquista

An Asturian Visigothic noble named Pelayos or Pelagius in 718 AD was elected leader by many of the ousted Visigoth nobles. Don Pelayos called for the remnant of the Christian Visigothic armies to rebel against the Moors and regroup in the unconquered northern Asturian highlands, better known today as the Cantabrian Mountains, in what is today the small mountain region in North-western Spain, adjacent to the Bay of Biscay.

Don Pelayos’ plan was to use the Cantabrian mountains as a place of refuge and protection from the invading Moors. He then aimed to regroup the Iberian Peninsula’s Christian armies and use the Cantabrian mountains as a springboard from which to regain their lands from the Moors. In the process, after defeating the Moors in the Battle of Covadonga in 722 AD, Pelayos was proclaimed king, thus founding the Christian Kingdom of Asturias and starting the war of reconquest known in Portuguese (and Spanish) as the Reconquista.

At the end of the ninth century, the region of Portugal, between the Rivers Minho and Douro, was freed or reconquered from the Moors by Don Vimara Peres on the orders of King Alfonso III of Asturias. Finding that the region had previously had two major cities –Portus Cale in the coast and Braga in the interior, with many towns that were now deserted, he decided to repopulate and rebuild them with Portuguese and Galician refugees and other Christians.

Thus, it was very easy for Don Vimara Peres to organize the region and elevate it to the status of County. Don Vimara Peres named the region he freed from the Moors, the County of Portugal after the region’s major port city – Portus Cale modern Oporto. One of the first cities Don Vimara Peres founded at this time is Vimaranes, known today as Guimarães – the “birthplace of the Portuguese nation” or the “cradle city” (Cidade Berço in Portuguese).

After annexing the County of Portugal into one of the several counties that made up the Kingdom of Asturias, King Alfonso III of Asturias knighted Don Vimara Peres, in 868 AD, as the First Count of Portus Cale (Portugal). The region became known as Portucale, Portugale, and simultaneously Portugália — the County of Portugal.

During the Reconquista period, Christians reconquered the Iberian Peninsula from Moorish domination. A victory over the Muslims at the Battle of Ourique in 1139 is traditionally taken as the occasion when the County of Portugal as a fief of the Kingdom of León was transformed into the independent Kingdom of Portugal.

Henry, to whom the newly formed county was awarded by Alfonso VI for his role in reconquering the land, based his newly formed county in Bracara Augusta (nowadays Braga), capital city of the ancient Roman province, and also previous capital of several kingdoms over the first millennia.

On 24 June 1128, the Battle of São Mamede occurred near Guimarães. Afonso Henriques, Count of Portugal, defeated his mother Countess Teresa and her lover Fernão Peres de Trava, thereby establishing himself as sole leader. Afonso then turned his arms against the Moors in the south. His campaigns were successful and, on 25 July 1139, he obtained an overwhelming victory in the Battle of Ourique, and straight after was unanimously proclaimed King of Portugal by his soldiers.

Afonso then established the first of the Portuguese Cortes at Lamego, where he was crowned by the Archbishop of Braga, though the validity of the Cortes of Lamego has been disputed and called a myth created during the Portuguese Restoration War. Afonso was recognized in 1143 by King Alfonso VII of León and Castile, and in 1179 by Pope Alexander III.

Afonso Henriques and his successors, aided by military monastic orders, pushed southward to drive out the Moors. At this time Portugal covered about half of its present area. In 1249, the Reconquista ended with the capture of the Algarve and complete expulsion of the last Moorish settlements on the southern coast, giving Portugal its present-day borders, with minor exceptions.

The reigns of Dinis I, Afonso IV, and Pedro I for the most part saw peace with the Christian kingdoms of Iberia, and thus the Portuguese kingdom advanced in prosperity and culture.

In 1348 and 1349 Portugal, like the rest of Europe, was devastated by the Black Death. In 1373, Portugal made an alliance with England, which is the longest-standing alliance in the world. This alliance served both nations’ interests throughout history and is regarded by many as the predecessor to NATO. Over time this went way beyond geo-political and military cooperation (protecting both nations’ interests in Africa, the Americas and Asia against French, Spanish and Dutch rivals) and maintained strong trade and cultural ties between the two old European allies. Particularly in the Oporto region, there is visible English influence to this day.

In 1383, John I of Castile, husband of Beatrice of Portugal and son-in-law of Ferdinand I of Portugal, claimed the throne of Portugal. A faction of petty noblemen and commoners, led by John of Aviz (later King John I of Portugal) and commanded by General Nuno Álvares Pereira defeated the Castilians in the Battle of Aljubarrota. With this battle, the House of Aviz became the ruling house of Portugal.

Portugal spearheaded European exploration of the world and the Age of Discovery. Prince Henry the Navigator, son of King João I, became the main sponsor and patron of this endeavour. During this period, Portugal explored the Atlantic Ocean, discovering several Atlantic archipelagos like the Azores, Madeira, and Cape Verde, explored the African coast, colonized selected areas of Africa, discovered an eastern route to India via the Cape of Good Hope, discovered Brazil, explored the Indian Ocean, established trading routes throughout most of southern Asia, and sent the first direct European maritime trade and diplomatic missions to China and Japan.

In 1415, Portugal acquired the first of its overseas colonies by conquering Ceuta, the first prosperous Islamic trade centre in North Africa. There followed the first discoveries in the Atlantic: Madeira and the Azores, which led to the first colonization movements.

Throughout the 15th century, Portuguese explorers sailed the coast of Africa, establishing trading posts for several common types of tradable commodities at the time, ranging from gold to slaves, as they looked for a route to India and its spices, which were coveted in Europe.

The Treaty of Tordesillas, intended to resolve the dispute that had been created following the return of Christopher Columbus, was signed on 7 June 1494, and divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between Portugal and Spain along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands (off the west coast of Africa).

In 1498, Vasco da Gama reached India and brought economic prosperity to Portugal and its population of 1.7 million residents, helping to start the Portuguese Renaissance. In 1500, the Portuguese explorer Gaspar Corte-Real reached what is now Canada and founded the town of Portugal Cove-St. Philip’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, long before the French and English in the 17th century, and being just one of many Portuguese Colonizations of the Americas.

In 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral discovered Brazil and claimed it for Portugal. Ten years later, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Goa in India, Ormuz in the Persian Strait, and Malacca, now a state in Malaysia. Thus, the Portuguese empire held dominion over commerce in the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic. Portuguese sailors set out to reach Eastern Asia by sailing eastward from Europe, landing in such places as Taiwan, Japan, and the island of Timor.

Although for a long period it was believed the Dutch were the first Europeans to arrive in Australia, very strong evidence points to the Portuguese discovery of Australia, in 1521.

The Treaty of Zaragoza, signed on 22 April 1529 between Portugal and Spain, specified the anti-meridian to the line of demarcation specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas.

All these factors made Portugal the world’s major economic, military, and political power from the 15th century until the late 16th century.

Portugal’s sovereignty was interrupted between 1580 and 1640. This occurred because the last two kings of the House of Aviz – King Sebastian, who died in the battle of Alcácer Quibir in Morocco, and his great-uncle and successor, King Henry of Portugal – both died without heirs, resulting in the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580.

Subsequently, Philip II of Spain claimed the throne and so became Philip I of Portugal. Although Portugal did not lose its formal independence, it was governed by the same monarch who governed the Spanish Empire, briefly forming a union of kingdoms. At this time Spain was a geographic territory. The joining of the two crowns deprived Portugal of an independent foreign policy and led to its involvement in the Eighty Years’ War between Spain and the Netherlands.

War led to a deterioration of the relations with Portugal’s oldest ally, England, and the loss of Hormuz, a strategic trading post located between Iran and Oman. From 1595 to 1663 the Dutch-Portuguese War primarily involved the Dutch companies invading many Portuguese colonies and commercial interests in Brazil, Africa, India and the Far East, resulting in the loss of the Portuguese Indian Sea trade monopoly.

In 1640, John IV spearheaded an uprising backed by disgruntled nobles and was proclaimed king. The Portuguese Restoration War between Portugal and the Spanish Empire, in the aftermath of the 1640 revolt, ended the sixty-year period of the Iberian Union under the House of Habsburg. This was the beginning of the House of Braganza, which reigned in Portugal until 1910.

Official estimates – and most estimates made so far – place the number of Portuguese migrants to Colonial Brazil during the gold rush of the 18th century at 600,000. This represented one of the largest movements of European populations to their colonies to the Americas during colonial times.

Disaster fell upon Portugal in the morning of 1 November 1755, when Lisbon was struck by a violent earthquake with an estimated Richter scale magnitude of 9. The city was razed to the ground by the earthquake and the subsequent tsunami and ensuing fires.

In 1762, Spain invaded Portuguese territory as part of the Seven Years’ War, but by 1763 the status quo between Spain and Portugal before the war had been restored.

In the autumn of 1807, Napoleon moved French troops through Spain to invade Portugal. From 1807 to 1811, British-Portuguese forces would successfully fight against the French invasion of Portugal, while the royal family and the Portuguese nobility, including Maria I, relocated to the Portuguese territory of Brazil, at that time a colony of the Portuguese Empire, in South America. This episode is known as the Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil.

With the occupation by Napoleon, Portugal began a slow but inexorable decline that lasted until the 20th century. This decline was hastened by the independence in 1822 of the country’s largest colonial possession, Brazil. In 1807, as Napoleon’s army closed in on Lisbon, the Prince Regent João VI of Portugal transferred his court to Brazil and established Rio de Janeiro as the capital of the Portuguese Empire. In 1815, Brazil was declared a Kingdom and the Kingdom of Portugal was united with it, forming a pluricontinental State, the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves.

As a result of the change in its status and the arrival of the Portuguese royal family, Brazilian administrative, civic, economical, military, educational, and scientific apparatus were expanded and highly modernized. Portuguese and their allied British troops fought against the French Invasion of Portugal and by 1815 the situation in Europe had cooled down sufficiently that João VI would have been able to return safely to Lisbon. However, the King of Portugal remained in Brazil until the Liberal Revolution of 1820, which started in Porto, demanded his return to Lisbon in 1821.

Thus he returned to Portugal but left his son Pedro in charge of Brazil. When the Portuguese Government attempted the following year to return the Kingdom of Brazil to subordinate status, his son Pedro, with the overwhelming support of the Brazilian elites, declared Brazil’s independence from Portugal. Cisplatina (today’s sovereign state of Uruguay), in the south, was one of the last additions to the territory of Brazil under Portuguese rule.

At the height of European colonialism in the 19th century, Portugal had already lost its territory in South America and all but a few bases in Asia. Luanda, Benguela, Bissau, Lourenço Marques, Porto Amboim and the island of Mozambique were among the oldest Portuguese-founded port cities in its African territories. During this phase, Portuguese colonialism focused on expanding its outposts in Africa into nation-sized territories to compete with other European powers there.

With the Conference of Berlin of 1884, Portuguese Africa territories had their borders formally established on request of Portugal in order to protect the centuries-long Portuguese interests in the continent from rivalries enticed by the Scramble for Africa. Portuguese Africa’s cities and towns like Nova Lisboa, Sá da Bandeira, Silva Porto, Malanje, Tete, Vila Junqueiro, Vila Pery and Vila Cabral were founded or redeveloped inland during this period and beyond. New coastal towns like Beira, Moçâmedes, Lobito, João Belo, Nacala and Porto Amélia were also founded. Even before the turn of the 20th century, railway tracks as the Benguela railway in Angola, and the Beira railway in Mozambique, started to be built to link coastal areas and selected inland regions.

Other episodes during this period of the Portuguese presence in Africa include the 1890 British Ultimatum. This forced the Portuguese military to retreat from the land between the Portuguese colonies of Mozambique and Angola (most of present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia), which had been claimed by Portugal and included in its “Pink Map“, which clashed with British aspirations to create a Cape to Cairo Railway.

The Portuguese territories in Africa were Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Portuguese Guinea, Angola, and Mozambique. The tiny fortress of São João Baptista de Ajudá on the coast of Dahomey, was also under Portuguese rule. In addition, Portugal still ruled the Asian territories of Portuguese India, Portuguese Timor and Macau.

Portugal’s international status was greatly reduced during the 19th century, especially following the Independence of Brazil. After the 1910 revolution deposed the monarchy, the democratic but unstable Portuguese First Republic was established, itself being superseded by the “Estado Novo” right-wing authoritarian regime. Democracy was restored after the Portuguese Colonial War and the Carnation Revolution in 1974. Shortly after, independence was granted to Angola, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe, East Timor, Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau.