https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veil_of_Veronica

https://treskia.wordpress.com/veil-of-veronica

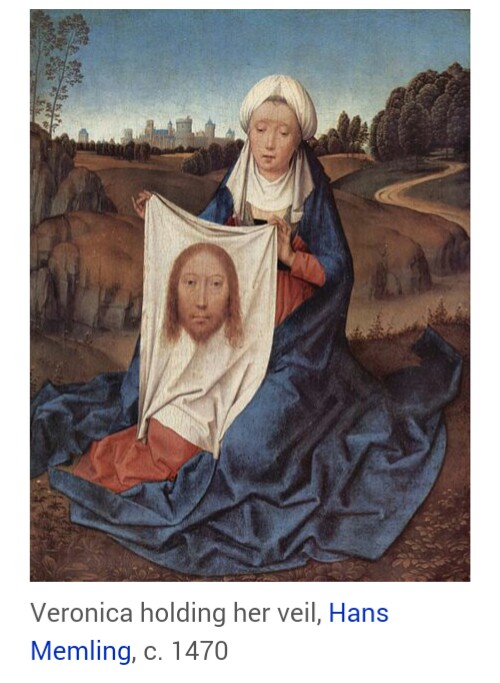

The Veil of Veronica, or Sudarium (Latin for sweat-cloth), often called simply “The Veronica” and known in Italian as the Volto Santo or Holy Face (but not to be confused with the carved crucifix Volto Santo of Lucca), is a Catholic relic of a piece of cloth which, according to legend, bears the likeness of the face of Jesus not made by human hand (i.e. an Acheiropoieton). Various existing images have been claimed to be the “original” relic, or early copies of it, but the evidently legendary nature of the story means that there are many fewer people, even among traditional Catholics, who treat claims of actual authenticity very seriously compared to the comparable relic of the Turin Shroud.

The final form of the Western legend recounts that Saint Veronica from Jerusalem encountered Jesus along the Via Dolorosa on the way to Calvary. When she paused to wipe the blood and sweat (Latin sudor) off his face with her veil, his image was imprinted on the cloth. The event is commemorated by the Sixth Station of the Stations of the Cross. According to some versions, Veronica later traveled to Rome to present the cloth to the Roman Emperor Tiberius and the veil possesses miraculous properties, being able to quench thirst, cure blindness, and sometimes even raise the dead.

The story is not recorded in its present form until the Middle Ages and for this reason, is unlikely to be historical. Rather, its origins are more likely to be found in the story of the image of Jesus associated with the Eastern Church known as the Mandylion or Image of Edessa, coupled with the desire of the faithful to be able to see the face of their Redeemer. During the fourteenth century it became a central icon in the Western Church – in the words of art historian Neil Macgregor – “From [the 14th Century] on, wherever the Roman Church went, the Veronica would go with it.”

There is no reference to the story of Veronica and her veil in the canonical Gospels; the story comes from centuries of tradition. The closest written reference is the miracle of Jesus healing the bleeding woman by touching the hem of Jesus’ garment (Luke 8:43-48); her name is later identified as Veronica by the apocryphal “Acts of Pilate“. The story was later elaborated in the 11th century by adding that Christ gave her a portrait of himself on a cloth, with which she later cured Tiberius. The linking of this with the bearing of the cross in the Passion, and the miraculous appearance of the image was made by Roger d’Argenteuil‘s Bible in Frenchin the 13th century, and gained further popularity following the internationally popular work, Meditations on the life of Christ of about 1300 by a Pseudo-Bonaventuran author. It is also at this point that other depictions of the image change to include a crown of thorns, blood, and the expression of a man in pain, and the image became very common throughout Catholic Europe, forming part of the Arma Christi, and with the meeting of Jesus and Veronica becoming one of the Stations of the Cross.

On the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem there is a small chapel, known as the Chapel of the Holy Face. Traditionally, this is regarded as the home of St Veronica and site of the miracle.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, the name “Veronica” is a colloquial portmanteau of the Latin word Vera, meaning truth, and Greek Icon meaning “image”; the Veil of Veronica was therefore largely regarded in medieval times as “the true image”, and the truthful representation of Jesus, preceding the Shroud of Turin.

The Vindicta salvatoris of the fourth century has been found dating to prior to the Middle Ages and there is no doubt that there was a physical image displayed in Rome in the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries which was known and venerated as the Veil of Veronica. The history of that image is however, somewhat problematic.

It has often been assumed that the Veronica was present in the old St Peter’s in the papacy of John VII (705-8) as a chapel known as the Veronica chapel was built during his reign, and this seems to have been the assumption of later writers. This is far from certain however as mosaics which decorated that chapel do not refer to the Veronica story in any way. Furthermore, contemporaneous writers make no reference to the Veronica in this period. It would appear however that the Veronica was in place by 1011 when a scribe was identified as keeper of the cloth.

However, firm recording of the Veronica only begins in 1199 when two pilgrims named Gerald de Barri (Giraldus Cambrensis) and Gervase of Tilbury made two accounts at different times of a visit to Rome which made direct reference to the existence of the Veronica. Shortly after that, in 1207, the cloth became more prominent when it was publicly paraded and displayed by Pope Innocent III, who also granted indulgences to anyone praying before it. This parade, between St Peter’s and The Santo Spirito Hospital, became an annual event and on one such occasion in 1300 Pope Boniface VIII, who had it translated to St. Peter’s in 1297, was inspired to proclaim the first Jubilee in 1300. During this Jubilee the Veronica was publicly displayed and became one of the “Mirabilia Urbis” (“wonders of the City”) for the pilgrims who visited Rome. For the next two hundred years the Veronica, retained at Old St Peter’s, was regarded as the most precious of all Christian relics; there Pedro Tafur, a Spanish visitor in 1436, noted:

On the right hand is a pillar as high as a small tower, and in it is the holy Veronica. When it is to be exhibited an opening is made in the roof of the church and a wooden chest or cradle is let down, in which are two clerics, and when they have descended, the chest or cradle is drawn up, and they, with the greatest reverence, take out the Veronica and show it to the people, who make concourse there upon the appointed day. It happens often that the worshippers are in danger of their lives, so many are they and so great is the press.Pedro Tafur, Andanças e viajes.

After the Sack of Rome in 1527, some writers recorded that the veil had been destroyed: Messer Unbano to the Duchess of Urbino say that the Veronica was stolen and passed around the taverns of Rome. Other writers however, testify to its continuing presence in the Vatican and one witness to the sacking states that the Veronica was not found by the looters.

Many artists of the time created reproductions of the Veronica, again suggesting its survival, but in 1616, Pope Paul V prohibited the manufacture of further copies unless made by a canon of Saint Peter’s Basilica. In 1629, Pope Urban VIII not only prohibited reproductions of the Veronica from being made, but also ordered the destruction of all existing copies. His edict declared that anyone who had access to a copy must bring it to the Vatican, under penalty of excommunication.

After that the Veronica disappears almost entirely from public view, and its subsequent history is unrecorded. As there is no conclusive evidence that it ever left St Peter’s, the possibility exists that it remains there to this day; this would be consistent with such limited information as the Vatican has provided in recent centuries.